Becoming American: a Political Memoir by Cary Lowe

Excerpt About Tom Hayden and Founding of CED

… Fred [Branfman] quickly arranged a lunch meeting for us at a Santa Monica restaurant on Ocean Avenue, near the pier. We lounged on a sunny patio, looking out at the ocean. Tom surprised me by launching into a description of his new interest in karate and his attempt, maybe for the first time, to get into good physical shape. Then, over soup and salads, we engaged in a freewheeling political discussion.

“Why did you run for the Senate?” I began. It seemed to me an act far removed from his earlier, more radical organizing days in the civil rights movement, the Newark ghetto, and the campaign to end the Vietnam War.

After he talked about his motivation for the campaign, I had a different question. “What do you want to accomplish with a statewide political organization?” He described being inspired by Upton Sinclair and Cesar Chavez, and his belief that an organization like that could push California politics in a more progressive direction for a generation to come.

Then Tom changed gears. Fred had told him a bit about me and my work, but he asked about my background and how I had gotten politicized. I told him about my campaign experiences, my evolution to opposing the Vietnam War, and my work with CIP. Eventually, we got into how my skills and experience fit into his vision. He didn’t try to persuade me directly. He painted a vision of California’s political future and invited me to put myself into it. I saw in him a natural organizer and politician, and I understand how he had become such an important figure in the anti-war movement.

By the end of lunch, I was sold. But we weren’t done.

We went back to the house that Tom occupied with his wife Jane Fonda, near the beach in the decayed but gentrifying Ocean Park neighborhood. Like the others around it, the two-story house filled its small lot and showed signs of recent painting and repairs. At the top of the front stairs, Fred stepped into the enclosed porch to retrieve some papers. He had been living there, on Tom and Jane’s front porch, since moving to California, so he could be close to them at all times. If that seemed eccentric then, I had much more to learn about Fred.

We found Jane waiting for us, sitting on a sofa in the living room, dressed in a casual but elegant pantsuit. Glancing around the room, I notice the furnishings looked comfortable, but old and a bit worn. Jane greeted me with a big smile and motioned for me to sit in a chair opposite her. That gesture put me at ease, even though I was meeting my first movie star.

I found Jane to be businesslike when it came to politics. She impressed me as informed, politically sophisticated, and unpretentious — different from her Hollywood image. And she asked good questions. What was my perspective on current state politics? Why did I want to work with them? What skills and experience did I bring?

Where Tom came across as high-energy and driven, Jane seemed calmer and more inquisitive. I sensed she was an important stabilizing influence on Tom.

After an hour or so of discussion, Jane leaned back and looked directly at me. “I hope you’ll join us,” she said, in a tone as friendly as it was sincere. “We’re going to do great things. You won’t regret it.”

Tom and Fred, who had been largely silent during my discussion with Jane, both smiled and nodded in my direction. I felt I had passed an important test and they were inviting me to join in an exclusive and important venture.

“I’m in,” I replied, nodding back at each of them in turn. …

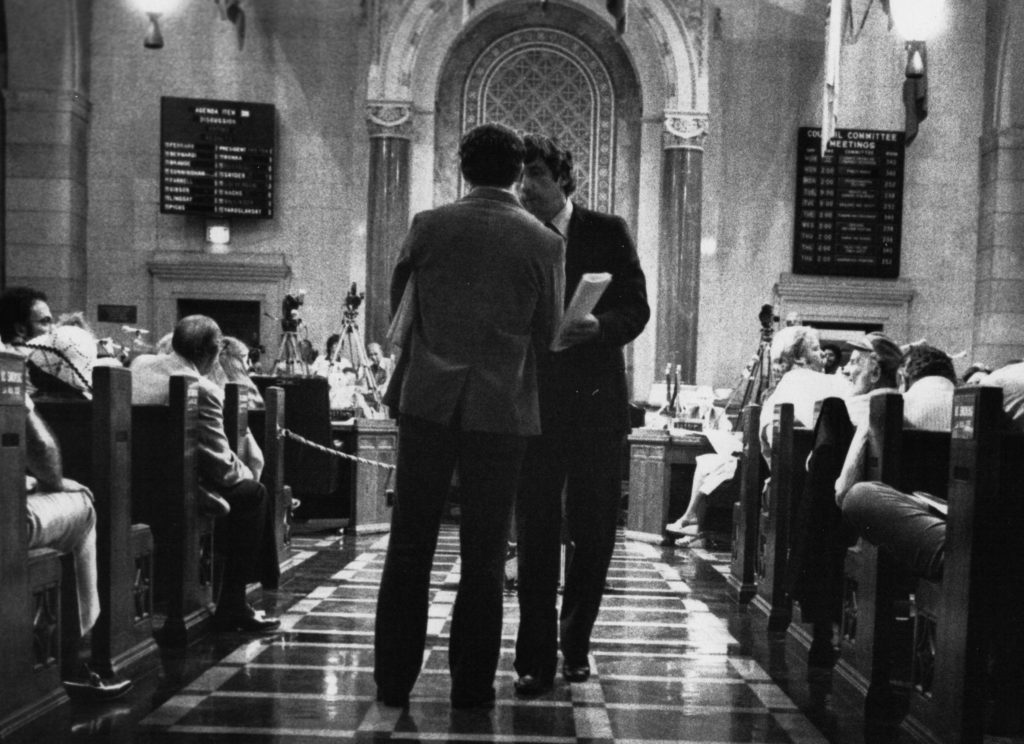

With Tom Hayden at Los Angeles City Council Meeting

With Jane Fonda.

We immediately began work on the planned Santa Barbara conference. While Hayden drafted a vision statement to be mailed out to activists statewide, as an invitation to come to the conference, Fred and I set to work drafting a two-volume set of “Working Papers on Economic Democracy.”

For three months, we labored over this, often late into the night, examining each sector of the California economy and theorizing how to make it more responsive to public needs and controls. I felt like I was back in graduate school, only this time my dissertation would be put to immediate use — and, hopefully, have an immediate impact.

In February 1977, over two hundred activists gathered at Santa Barbara City College. They came from every part of the state, from the North Coast, the Bay Area, the Central Valley, LA, and San Diego. They covered the liberal-to left-political spectrum. Earnest-looking college professors and students. Energetic community organizers. Black activists sporting dashikis and huge Afros. Sunburned farmworkers in jeans and flannel shirts. Aging radicals looking for one more cause to champion and young activists engaged in their first campaigns. Even a sprinkling of elected officials. All had received our Working Papers before coming.

For an entire day, they broke up into workshops, focused on housing, energy, agriculture, education, environment, natural resources, affirmative action, and a dozen other topics. Each group, meeting in a separate classroom, debated, argued, and sometimes agreed. By late afternoon, they had adopted dozens of policy positions to be presented the next day to the entire conference.

I stayed up all night supervising a gang of transcribers, typists, and copiers, to convert the notes from the workshops into a set of draft resolutions, in preparation for debate and voting by the entire assembly in the morning. The clicking of manual typewriters and the whirring of copying machines drowned out conversation. Most smiled as they worked, excited at what had emerged from the workshops. Some grew upset over what they read and wanted to revise the text, but I had to veto that. We didn’t finish until after sunrise, by which time we all had gotten a bit testy from fatigue and too much coffee.

As the conferees drifted into the main meeting hall for the early morning plenary session, we handed them each the printed, stapled product of their work the day before and our work through the night. How different, I thought, from how issues platforms get developed at the major political party conventions.

Hayden chaired the plenary. Guiding two hundred passionate activists through a discussion of at least a couple hundred resolutions took every ounce of his political organizing experience. Some topics, like establishing a renewable energy sector and promoting residential rent control, went through smoothly. Others, like public ownership of certain industries versus greater corporate shareholder rights, became mired in controversy. From a seat near the front of the hall, I swiveled in all directions to see the speakers and hear their comments. With adoption of each plank of the emerging platform, I felt my level of excitement rising, like watching the returns come in on election night.

By late morning, we got bogged down in political minutia. As the clock closed in too rapidly on a noon deadline to adjourn, Tom pulled a trick from his back pocket. Going off script, he announced that we would take a break from the debate and hear a speech by John Maher, head of the San Francisco-based Delancey Street Foundation. I felt confused at this turn of events but I knew to trust Tom’s organizer instincts.

A squat Irishman with a boxer’s rumpled face, a New York accent, and a major attitude, Maher worked with ex-cons, drug addicts, former hookers, and other street people, helping them straighten out their lives and get conventional jobs. He sounded as tough as he looked. A seasoned organizer, like Tom, he would soon help his brother Bill get elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. The moment Hayden announced him, Maher made his way up to the stage and launched into a stem-winder of a speech that quickly had the attention of the whole room.

“The people I work with,” he told the crowd, “they don’t understand all the fine points of the subjects you’re debating. And sometimes they don’t appreciate the etiquette that’s expected of people in political circles. But we’ll work on your causes and we’ll walk your picket lines, because we know we’re all in this together.”

Maher talked for half an hour, but it felt like mere minutes. Scattered voices punctuated his statements, like intermittent call and response. The air in the room felt heavier and the crowd murmured more and more loudly. I pictured Abraham Lincoln or Huey Long energizing a campaign rally. Reaching the finale, Maher’s voice rose to an angry pitch.

“Remember!” he thundered. “Man for man, we’re a better gang than the other side. We’re going to take them, we’ll take them hard!” I had been leaning forward, listening closely. Now I suddenly sat upright, as if hit by an electric shock.

Maher looked down and his shoulders dropped. The crowd paused briefly, then broke into wild applause. The building seemed to shake. Waiting for that moment, Hayden leaped back to the podium.

“I move to adopt the remaining resolutions by acclamation,” Fred Branfman yelled from the front row. Someone else seconded that and, before anyone could object, yet another person called the question. In moments, a voice vote overwhelmingly approved the motion. A few people protested, demanding a chance to debate further. Too late. We were done. I looked up at Tom still standing at the podium, wearing a wide smile. Our eyes met for a moment, and we nodded in unison. At that moment, it felt almost as momentous as the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Looking back, I know that was a burst of youthful overenthusiasm, but I had just seen the start of the first progressive statewide movement in California in over half a century.

We had a mandate and a program. Days later, back in LA, Tom publicly announced the launching of the Campaign for Economic Democracy, based on the principles he had laid out in the conference invitation and the resolutions adopted at the meeting. Chapters quickly came together in a dozen cities, rising out of the ashes of the Hayden for Senate campaign. Separate chapters of Students for Economic Democracy formed on half a dozen college campuses. And a network of other activist groups quickly connected to the newly formed CED — black and Chicano community activists, tenant organizations, environmentalists, and more.

Soon after, Jane Fonda bought Laurel Springs Ranch, a former religious camp in the mountains overlooking Santa Barbara. With bunkhouses, a dining hall, meeting rooms, and recreational facilities, it provided a perfect retreat location for statewide CED meetings and all kinds of other political gatherings. We loved the irony of being just down the road from Ronald Reagan’s Rancho Cielo. Jane and Tom had a separate small house on the property, as did a caretaker couple. After a long day of meetings, we played baseball, soaked in a huge hot tub, or drove down to San Marcos Pass for a beer at Cold Spring Tavern, a historic one-time stagecoach stop.

I wasn’t sure yet where this would lead, but I knew I had hitched my wagon to something that had great potential. Now, I just needed to make the most of it and hang on for the ride.

Cary Lowe, Writer is proudly powered by WordPress